What does the word ‘beauty’ mean to you? Is it something refined, unblemished, idealised, perfect, youthful? Is it a landscape, a painting, a rarefied object, a person, a way of life? Beauty is impossible to define. Famously, it is in the eye of the beholder; up to each of us to decipher it for ourselves.

I’ve spent my life studying art and artists, who are, in many ways, conduits for showing us beauty in the form of something tangible – whether it be in a painting, photograph, song, poem or film. Digging deep into their imagination, artists help us attach ideas or meanings into realised forms, enabling us to understand how we feel about something or someone. While it can be extraordinary in so many ways, it can also shape said ideas and create visual templates that can become the ‘default’ – something to consider when we are thinking about which perspective we are so often reading or looking at something from.

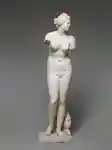

For example: where do our default ideas of ‘beauty’ stem from? In ancient Greece, beauty was a divine concept, worshipped in the form of Aphrodite, goddess of love, desire and beauty. When artists came to sculpt her, they pictured her as soft, youthful, unblemished, symmetrical. It became their idea of perfection embodied, and reinforced ideas about what the most desirable woman – and beauty – should be.

Marble statue of Aphrodite, 1st or 2nd Century CE. Credit: The Met

I’ve spent my life studying art and artists, who are, in many ways, conduits for showing us beauty in the form of something tangible – whether it be in a painting, photograph, song, poem or film. Digging deep into their imagination, artists help us attach ideas or meanings into realised forms, enabling us to understand how we feel about something or someone. While it can be extraordinary in so many ways, it can also shape said ideas and create visual templates that can become the ‘default’ – something to consider when we are thinking about which perspective we are so often reading or looking at something from.

For example: where do our default ideas of ‘beauty’ stem from? In ancient Greece, beauty was a divine concept, worshipped in the form of Aphrodite, goddess of love, desire and beauty. When artists came to sculpt her, they pictured her as soft, youthful, unblemished, symmetrical. It became their idea of perfection embodied, and reinforced ideas about what the most desirable woman – and beauty – should be.

Marble statue of Aphrodite, 1st or 2nd Century CE. Credit: The Met

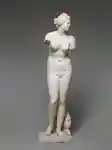

The Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli, 1485 ca. Credit: The Uffizi

Later in ancient Rome, they absorbed Aphrodite into Venus, depicting her just as the Greeks had. In the Renaissance, a movement that adopted these classical ideas (c. 14th – 17th centuries), Venus enjoyed a revival, and was among the most popular subjects, captured by the likes of Titian and Botticelli, who crafted her in an ‘idealised’ form and often as a spectacle for the male gaze. While painting Venus was to celebrate beauty, it also normalised and codified a specific image that can be traced all the way to how women are still, in many ways, upheld in the media today.

This is why I believe it’s so important to look at art from a broad perspective – something finally changing thanks to the tireless work of so many who have helped other voices enter the canon. Because when we do, our ideas of meanings change and expand, which make people feel more seen. It’s not unlike the world of cosmetics and make-up: the more we see different people trying out different looks, the more exciting and rich our idea of beauty can be. For those growing up today, these appearances will become the norm.

We may live in a world that, much like ancient Greece, prioritises a particular kind of beauty, but if we dare to look beyond, to pause, question and analyse, our perception of beauty, and of the world itself, can be radically overturned.

The Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli, 1485 ca. Credit: The Uffizi

Later in ancient Rome, they absorbed Aphrodite into Venus, depicting her just as the Greeks had. In the Renaissance, a movement that adopted these classical ideas (c. 14th – 17th centuries), Venus enjoyed a revival, and was among the most popular subjects, captured by the likes of Titian and Botticelli, who crafted her in an ‘idealised’ form and often as a spectacle for the male gaze. While painting Venus was to celebrate beauty, it also normalised and codified a specific image that can be traced all the way to how women are still, in many ways, upheld in the media today.

This is why I believe it’s so important to look at art from a broad perspective – something finally changing thanks to the tireless work of so many who have helped other voices enter the canon. Because when we do, our ideas of meanings change and expand, which make people feel more seen. It’s not unlike the world of cosmetics and make-up: the more we see different people trying out different looks, the more exciting and rich our idea of beauty can be. For those growing up today, these appearances will become the norm.

We may live in a world that, much like ancient Greece, prioritises a particular kind of beauty, but if we dare to look beyond, to pause, question and analyse, our perception of beauty, and of the world itself, can be radically overturned.

So how do we find beauty? Perhaps it’s as simple as stopping just for a moment. Artists can teach us this. They teach us about bending time, how to look slowly and with intention. They remind us that ideas – like beauty – aren’t fixed. It’s found and reimagined every time we pay attention. I learnt this from two artists, Sally Mann and Agnes Martin, who may have differing visions of the world, yet reveal something profound when we think about the meaning of beauty.

Hailed for her images of nature in the American South or intimate portrayals of her children, Mann gets me to realise that beauty is something that is alive, because it cannot last forever. While her scenes are of something beautiful – like the youth of a human or the shape of a tree – they are also of something ephemeral. It seems Mann is trying to freeze a moment so precious, because, by its very nature, it will not last forever.

As she wrote in her memoir, Hold Still:

“As for me, I see both the beauty and the dark side of things; the loveliness of cornfields and full sails, but the ruin as well. And I see them at the same time, at once ecstatic at the beauty of things, and chary of that ecstasy.

The Japanese have a phrase for this dual perception: mono no aware. It means ‘beauty tinged with sadness,’ for there cannot be any real beauty without the indolic whiff of decay.

For me, living is the same thing as dying, and loving is the same thing as losing, and this does not make me a madwoman; I believe it can make me better at living, and better at loving, and, just possibly, better at seeing.”

Another take is Agnes Martin, the American artist hailed for her softly applied, minimalist canvases of grids and pastel-coloured lines. Martin gets me to understand that beauty is an emotional response, because what makes beauty ‘real’ is its ability to make you ‘feel’ – it’s in the mind, not the eye. As she said:

“When I think of art, I think of beauty. Beauty is the mystery of life. It is in the mind, not in the eye. In our minds, we have an awareness of perfection that leads us on. The response to beauty is emotion. Sometimes very subtle emotions of which we are almost not aware, and sometimes our most powerful emotions... Beauty is very much broader than just to the eye. It is our whole, positive response to life.”

To train oneself to look at art is the same as training oneself to reflect, pause and question. How will you think about beauty anew? Where will you look?

Katy Hessel is an acclaimed art historian, curator, and author of The Story of Art Without Men and How To Live An Artful Life (Nov, 2025). As founder of The Great Women Artists on Instagram and the Podcast, Katy brings her bold, feminist lens to the Archive - reimagining beauty culture through untold stories and shifting the spotlight toward women in history and art.

Katy Hessel is an acclaimed art historian, curator, and author of The Story of Art Without Men and How To Live An Artful Life (Nov, 2025). As founder of The Great Women Artists on Instagram and the Podcast, Katy brings her bold, feminist lens to the Archive - reimagining beauty culture through untold stories and shifting the spotlight toward women in history and art.